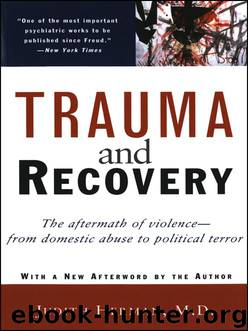

Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence--From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror by Judith L. Herman

Author:Judith L. Herman [Herman, Judith L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780465004058

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 1997-05-30T00:00:00+00:00

THE THERAPIST’S SUPPORT SYSTEM

The dialectic of trauma constantly challenges the therapist’s emotional balance. The therapist, like the patient, may defend against overwhelming feelings by withdrawal or by impulsive, intrusive action. The most common forms of action are rescue attempts, boundary violations, or attempts to control the patient. The most common constrictive responses are doubting or denial of the patient’s reality, dissociation or numbing, minimization or avoidance of the traumatic material, professional distancing, or frank abandonment of the patient. Some degree of intrusion or numbing is probably inevitable.48 The therapist should expect to lose her balance from time to time with such patients. She is not infallible. The guarantee of her integrity is not her omnipotence but her capacity to trust others. The work of recovery requires a secure and reliable support system for the therapist.49

Ideally, the therapist’s support system should include a safe, structured, and regular forum for reviewing her clinical work. This might be a supervisory relationship or a peer support group, preferably both. The setting must offer permission to express emotional reactions as well as technical or intellectual concerns related to the treatment of patients with histories of trauma.

Unfortunately, because of the history of denial within the mental health professions, many therapists find themselves trying to work with traumatized patients in the absence of a supportive context. Therapists who work with traumatized patients have to struggle to overcome their own denial. When they encounter the same denial in colleagues, they often feel discredited and silenced, just as victims do. In the words of Jean Goodwin: “My patients don’t always believe fully that they exist, nor, much less, that I do. . . . This is made all the worse when my fellow psychiatrist treats me and my patients as though we don’t exist. This last is done subtly, without overt brutality. . . . If it were only one time, I would not worry about being extinguished, but it is one hundred and one hundred hundreds, one thousand thousand tiny acts of erasure.”50

Inevitably, therapists who work with survivors come into conflict with their colleagues. Some therapists find themselves drawn into vituperative intellectual debates over the credibility of the traumatic syndromes in general or of one patient’s story in particular. Countertransference responses to traumatized patients often become fragmented and polarized, so that one therapist may take the position of the patient’s rescuer, for example, while another may take a doubting, judgmental, or punitive position toward the patient. In institutional settings the problem of “staff splitting,” or intense conflict over the treatment of a difficult patient, frequently arises. Almost always the subject of the dispute turns out to have a history of trauma. The quarrel among colleagues reflects the unwitting reenactment of the dialectic of trauma.

Intimidated or infuriated by such conflicts, many therapists treating survivors elect to withdraw rather than to engage in what feels like fruitless debate. Their practice goes underground. Torn, like their patients, between the official orthodoxy of their profession and the reality of their own experience, they choose to honor the reality at the expense of the orthodoxy.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Rewire Your Anxious Brain by Catherine M. Pittman(17619)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11953)

The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli(8897)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7873)

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza(7142)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(6684)

The Road Less Traveled by M. Scott Peck(6671)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(6667)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6511)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6434)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(6341)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6275)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(5828)

Daring Greatly by Brene Brown(5679)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4762)

Grit by Angela Duckworth(4760)

Men In Love by Nancy Friday(4366)

Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi(4078)

The Four Tendencies by Gretchen Rubin(4042)